You might have the most interesting premise in the world accompanied by extensively planned worldbuilding, plot diagramming, and mapmaking, but if you don’t have interesting characters, your book will not be interesting.

But what makes a compelling character? How do you write excellent characterization, even if you don’t just happen to think up an interesting character about whom to write?

In this article, we’ll cover what characterization is, how you can master it, and where you can find great examples of it in TV shows and novels. Let’s get started!

- What is characterization?

- How to use characterization

- Mistakes to avoid when using characterization

- Examples of good characterization

What is characterization

Characterization is the essence of a character. It’s about capturing what defines them and giving them life. In less words, the unique and fascinating qualities that makes us love or hate them.

Characterization plays a pivotal role in literature, film, and storytelling as a whole. It serves as the bridge that connects a character’s actions, words, and thoughts to the audience, allowing us to relate to and understand the characters on a deeper level. Think of it as the paint on a canvas that gives depth and color to the story, making it vibrant and engaging.

Authors and creators use a variety of techniques to develop characters. These may include providing detailed descriptions of a character’s appearance, delving into their background, and exposing their motivations and desires. Through these techniques, the audience gains insight into the character’s inner workings, enabling a more profound emotional connection with the story’s protagonists and antagonists alike.

How to use characterization

So, how do you use characterization—in other words, how do you create compelling characters?

How to create a character

A note: these things might not be included in your book—in fact, some of the really basic stuff probably won’t be. But it’s important for you to keep in mind as the author, since it informs how the character will react to the plot as it unfolds.

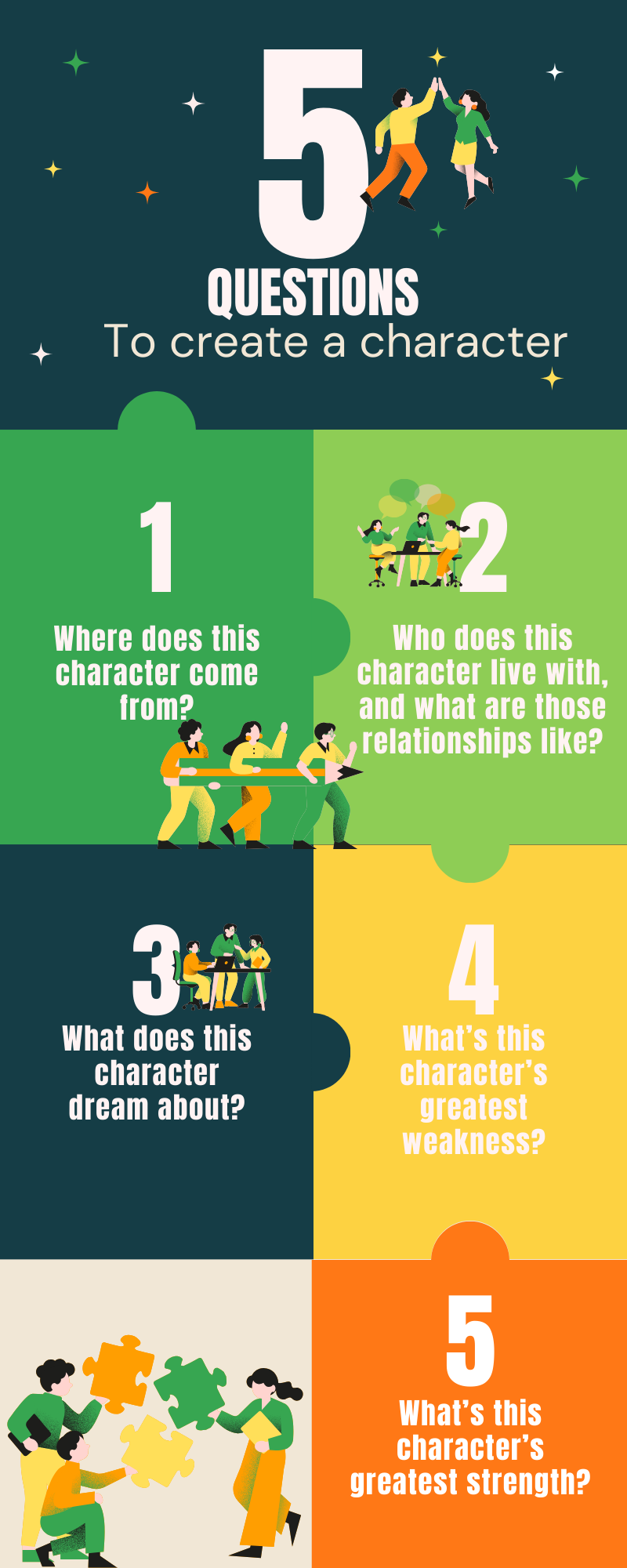

Ask yourself the following questions when creating your character:

Where does this character come from?

Think about where this character comes from. If this is a fantasy world, think about their place in it—are they a wealthy monarch, a comfortable merchant, or a peasant? Did they start out that way, and if not, how did they end up where we find them at the start of the novel?

Knowing the character’s background will inform much of how that character acts. Someone born and raised wealthy, for example, is going to interact with poverty in a way that’s much different from someone who grew up in poverty. And whether you’re reading a fantasy novel or a contemporary one, readers will pick up on the difference, and a character acting out of sorts will feel inauthentic.

Who does this character live with, and what are those relationships like?

What’s the character’s living situation? If they’re a child, do they live with their parents, or are they with guardians? How did that come to be? It’s also important to consider how those relationships are—consider whether the character gets along with their parents, if they live with their parents, and if they don’t, what it is they argue about.

If the character is an adult living alone, you might have to consider how they’re managing that if they live in a big city where rent is generally exorbitantly expensive. If they’re living with roommates, who are they living with, and are they getting along? Why or why not?

What does this character dream about?

This is going to be more than one thing, obviously, and it should stem effortlessly from their background and personality. Maybe they want to go to art school, and along with that, they want their parents to be understanding about their decision to go to art school.

What your character wants should be in direct conflict with the plot of the novel. Because of the plot, they can’t achieve their dreams—this is why they have to do the plot in the first place, or why the story exists.

What’s this character’s greatest weakness?

The plot will provide some friction between the character and their goals, but there should also be internal conflict. What’s this character’s greatest weakness, or the thing about them that’s holding them back from realizing their potential and saving the day?

In Shrek, it’s Shrek’s inability to be emotionally vulnerable. He wants everyone to keep out of his swamp and leave him alone. He’s mean, unpleasant, and goes out of his way to fulfill the image of ‘scary ugly ogre’ which society enforces upon him because it’s easier than admitting the truth: he wants connection with someone else. He wants a loving relationship with someone who understands him.

What’s this character’s greatest strength?

What’s your character’s greatest advantage? They probably don’t know about it yet—their insecurity is likely getting in the way when we meet them at the start of the story. This is usually something like patience, perseverance, kindness, or a strong will to do good. It’s the thing which they’ll ultimately discover was with them all along, and which is instrumental in saving the day and doing the plot.

How to create a cast of characters

If you’ve ever tried to write an ensemble cast, you know how hard it can be to keep each character essential, distinct, and memorable. Here are some questions to ask yourself:

How is each character essential to the story?

Sometimes, it’s tempting to include characters for the sake of wanting to write a certain dynamic—you love stone-faced grizzly dudes with their giggly sidekicks, so you give your grizzle protagonist a giggly sidekick. But, along the way, you forget to give that sidekick anything to do, so they end up just kind of standing around, delivering wisecracks, and getting on everyone’s nerves.

Each character should serve a role in the story. A sidekick should be instrumental in the protagonist’s internal journey—Donkey, for example, is a comedic sidekick, but he’s also a battering ram for Shrek’s emotional barriers, so he’s important to have around.

How are they different and alike?

What makes each character distinct, and what do some characters have in common? If two characters come from radically different backgrounds—say one character is from a group which has more social power than another group—it will likely impact the way they interact and the way they form a friendship, if a friendship is to be formed.

With friends, characters should have enough in common that they can relate to one another while not rendering the other redundant. In other words, if two characters are basically interchangeable—you could take one out and the plot wouldn’t change—you don’t need both.

Mistakes to avoid when using characterization

Here are a few things to watch out for when you’re creating your characters:

Making characters one-dimensional

Characters should have distinct traits which make them unique—that’s the whole point—but you don’t want them to be one-note tricks. If a character is only ever angry, and that’s their whole thing, and they only ever react in anger, it starts to feel juvenile, predictable, and boring.

People are complicated! This should reflect in your writing.

Not doing your research

If you’re writing about characters based on people whose experiences you do not share—for example, if you’re a straight person writing a gay or trans character—you’ve got some research to do. Read about these people’s experiences, read books by these people, and find people within that group to beta read your work. When they have critiques about how you’ve written them, be open to that, and be ready to do some heavy editing and internal work.

If you don’t do this, you’re potentially going to play into harmful stereotypes, and this kind of bad representation is pretty inexcusable in the age of Google dot com.

Making characters inconsistent

Characters shouldn’t be so predictable that they’re boring, but the things they do should make sense. If a character changes the way they approach a specific problem or how they treat a specific group of people, it should be clear why they’ve undergone that growth. Otherwise, we’re left feeling unsure about who this character is, and that makes it hard to connect with them.

Making character goals and inner worlds unclear

Speaking of which: while you don’t want to spoon-feed your reader by blatantly beating them over the head with your character’s hopes and dreams, you do want it to be clear what your character wants, how they’re feeling, and why. This is kind of the whole point of a character. If we can’t tell how a character feels, then we have no real way of investing in their next move.

Making characters stagnant

This is a big issue I see in contemporary published novels, and it’s a doozy: main characters should undergo change because of their journey. They should make mistakes and learn from them, grow wiser, figure out things about themselves and the world, and become different as a result. If a character floats through the plot perfectly and unaffected, effortlessly winning every conflict they come across and never really changing as a person, the reading experience is ruined. It’s not interesting to see what happens next if there’s no reason to think the character won’t just dance right through, unfazed.

Examples of good characterization

Here are some places you can find expertly crafted characters:

Avatar: The Last Airbender

Every main character in Avatar: The Last Airbender has a distinct personality, distinct motives and goals, and distinct internal and external journey. Aang, for example, is a child pacifist facing a militant empire—this means he not only has to grow up (which is, honestly, enough on its own), but he also has to master all four elements and defeat Firelord Ozai, all without sacrificing his pacifist ideals.

ATLA is also a great example of how to manage an ensemble cast. Characters have distinct elements assigned to them via their bending abilities, and even characters who can’t bend have distinct weaponry (“fan and sword!”), so when they head into a fight, they all have a role to play.

Normal People by Sally Rooney

Normal People features two main characters, Marianne and Connell, and Rooney uses an up-close writing approach to showcase their characterization. Since we’re so deep in their heads, we’re able to understand these characters’ motives and goals—even when they misstep, it’s obvious to us why they’ve done that, and it leaves us wondering whether they’ll realize their mistake and come clean with themselves.

Stone Blind by Natalie Haynes

In Stone Blind, Natalie Haynes has to manage an ensemble cast, and she has to manage a cast of characters with whom the audience already likely has a relationship. We’ve heard of the gods of Olympus, and we’re being asked to reimagine them.

Haynes nails her characterization using two major techniques. First, she acknowledges the history the reader likely has with the gods and deliberately points out the ‘true story,’ or the different story she’s telling.

She also makes her characters very consistent—the good things about characters, as is so often the case with people, are often also the things which cause their downfall. Medusa’s kindness, for example, is her greatest asset, but it’s also what gets her killed. Perseus’s stubbornness and single-mindedness makes him charming, but it eventually makes him unsettling.